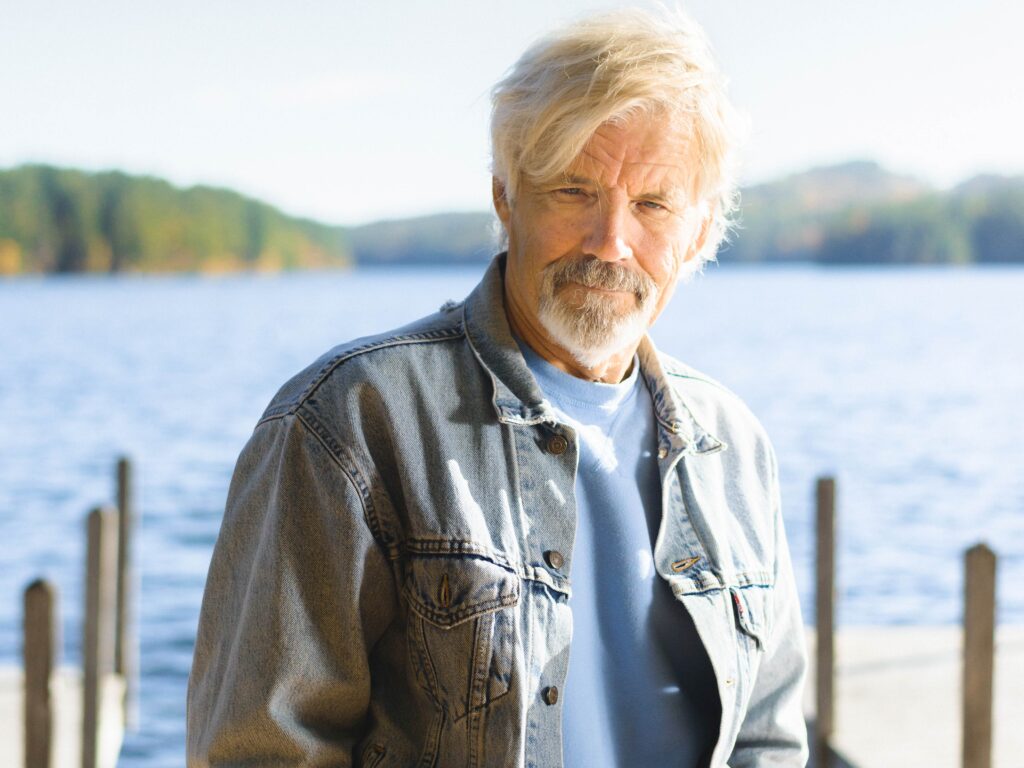

Ernest Thompson was only 28 when he wrote the play he’s perhaps best known for: On Golden Pond, the story of a retired university professor named Norman Thayer who is slowly succumbing to dementia but who agrees, together with his wife, to watch after his young grandson for a summer. Initially wary, the two end up becoming friends as well as family thanks to shared fishing adventures (and misadventures). Despite Norman’s failing health — he suffers a cardiac incident in the course of the play, as well as suffering a slow mental decline — the play ends on a note of hope and grace.

Thompson adapted his play for a movie that’s still renowned today for its casting of Henry Fonda and Katharine Hepburn. That film won Thompson the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay, as well as garnering dual wins for Best Actor and Best Actress for Ford and Hepburn.

That’s a major accomplishment — but Thompson hasn’t rested on his laurels. He hasn’t had time; over the last four and a half decades, he’s written twenty plays (thirteen full-length and seven short works), two novels (his newest is due out this fall), and a dozen screenplays for TV and movie-house projects. Oh, and songs; Thompson has written many, many songs, often original works used in his plays, and he’s collaborated on his tune smithing with everyone from Carly Simon, Joan Osborne and Christine Ohlman (The Beehive Queen from SNL) as well as Justin Jaymes, Dave Henderson, Marc Elbaum, John Davidson and Griffin William Sherry.

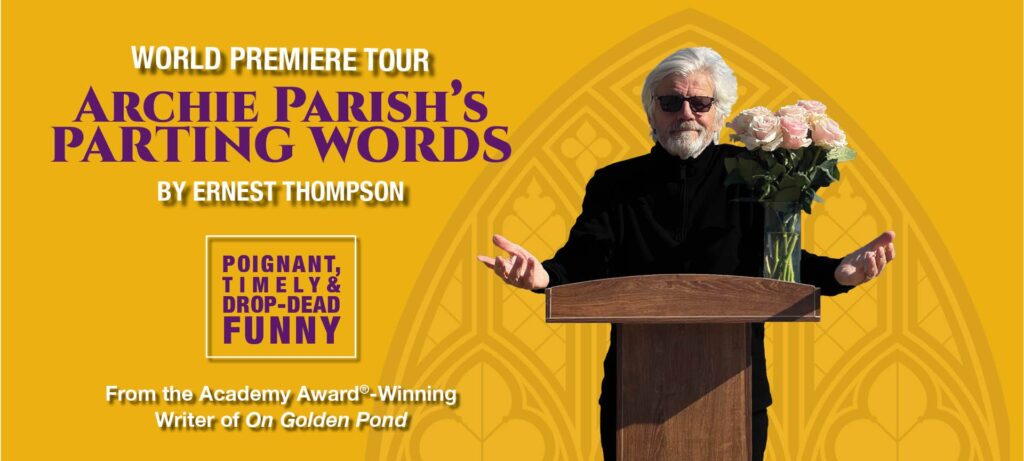

The New Hampshire resident’s newest play, “Archie Parish’s Parting Words,” is a solo show with a wealth of characters — some of them dead, all of them portrayed in the play’s rolling world premiere, continuing August 2 at The Park Theatre in Jaffrey, NH (followed by a Sept. 7 performance at The Rex Theatre in Manchester, NH). Title character Archie Parish is an older gent who, after delivering an outrageous, no-holds-barred eulogy, begins to make something of a career out of speaking at funerals. But how well did he know the deceased? Did the stories he tells ever happen? And what drives his compulsion to serve as a speaker for the dead, especially when his own life may be drawing to a close?

Disarmingly funny, yet unsparing, “Archie Parish’s Parting Words” reads on its surface like a tale of regret over opportunities missed and desperation to mend the past, but it also contains fathoms of deep reflection on identity, relationships, meaning — the big questions, in other words, that make human life the mystery and marvel that it is.

Ernest Thompson took a few minutes to chat with Theater Mirror about his new work, look back at On Golden Pond, and come full circle with his thoughts on playing Norman Thayer in an upcoming Broadway revival of his most famous work.

Theater Mirror: Let me get the inevitable On Golden Pond question out of the way first.

Ernest Thompson: Only one? Okay, let’s do it!

Theater Mirror: You wrote that play when you were still in your 20s, then you wrote the screenplay for the film version starring Katharine Hepburn and Henry Fonda, for which you won an Oscar. You were somewhat older in 2001 when you directed a live televised performance of “On Golden Pond” with Christopher Plummer and Julie Andrews. Did the intervening years change how you thought of the characters in the material?

Ernest Thompson: They did. And, you know, I’m still thinking about it. As you may have heard, I’m doing the play on Broadway this coming season. I’ve had 47 years of a lab study of “On Golden Pond,” and it’s fascinating to me because, you know, it used to be people would say, “How could someone so young know anything about old people?” I don’t get asked that question anymore, but I never had an answer. I’ve always been fascinated by people older than I. It’s hard now to find anybody older than I, but I just love hearing their perspective, their wisdom, their struggles, and all of that, starting with my dad, who died way too young at 70.

Theater Mirror: What are you looking forward to bringing to the role of Norman in the Broadway revival?

Ernest Thompson: The key thing that I knew intuitively, but couldn’t articulate, was that Norman Thayer was that guy who opened doors and windows for his students. For 40 years or more, Norman Thayer stood in front of classrooms and lecture halls at an Ivy League college and regaled students with great stories of literature. Fifteen years before the play starts, he’s lost his audience. Whom does he talk to? I never see him played that way. What happens is that people play [On Golden Pond] for the comedy. I play him now with much more empathy towards what he is going through. It’s impossible not to get drawn into the emotion of On Golden Pond, but still, it’s funnier if you play the complete pathos that underlies all of that.

Theater Mirror: There is also a combination of humor and pathos and some deep philosophical meditation in Archie Parish’s Parting Words — and you’re playing all the characters.

Ernest Thompson: I am, yeah. I don’t have anybody else to blame it on when I screw something up.

Theater Mirror: How did the experience of being older now translate into writing this new play, as well as acting in it?

Ernest Thompson: Same thing. In theory, we get slightly wiser as we get older, but that doesn’t mean our underlying qualities, whatever they are, go away. And so with Archie: He’s got stuff to work through, and in his case, it’s a secret.

I love that, as a storyteller, thinking, “Something is going on here, but we don’t know what yet.” Archie just seems like an overage smart-ass until we get down to the heart of what his situation is. I’ve been around for a long time, and I have experienced pain and loss, as we all do, and I just thought it was an interesting take that a guy has to look into other windows to find himself, and to observe and listen to other people’s stories until, eventually, he gets to his truth.

Theater Mirror: That’s a key observation on what’s happening in the play. But there’s another key as well, I think — the play is interrogating what it means to think we know another person. Not to make a eulogy for them, that is, but to be married to them, to work with them, to deal with them on a daily basis.

Ernest Thompson: I don’t know if you picked up that line, but Archie does say that in his penultimate eulogy… he says, “I also didn’t know the man in the box, which is true of many of us at many funerals, even if we were related to the person or married to them.” That is haunting, to think we don’t really know [someone else]. As the character of Gwendolyn says, “Everybody says we’re born alone, we die alone, but I’ve lived my entire life alone,” and that’s an interesting take on it, too. What is the person who doesn’t have the luxury of that sparring partner or that support system? How does that person get through? How did she find her way? All of which I am just fascinated by. I am the annoying person in every room who asks questions because I’m curious, and I hope I always will be. One learns so much from just shutting up and listening.

Theater Mirror You have been quite prolific in your career. Do you think that, in the full corpus of your work, you’ve been describing an arc of your life — an arc of narrative or philosophical reflections?

Ernest Thompson: I’m probably not quite that smart, but I think unconsciously that is true. I think there’s a central character in many of my pieces that is the essence of myself. I can remember when “On Golden Pond” came out, and people would say, “Who are you in that play? The kid? Are you the daughter?” I always knew I was Norman.

And Norman is just a variation on a theme, you know. In [the novel] The Book of Maps, I [write about] a smart-ass out-of-work screenwriter, no imagination whatsoever, but he’s got a lot of my personality and life experience. And here we are with Archie; it’s the same thing, but it was also the Katharine Hepburn/Shirley MacLaine character in The West Side Waltz, an acerbic, defensive, charming, irresistible character. I just described myself, of course.

[Laughter]

It’s that methodology that uses humor as a cattle prod to keep people at a distance, but also, I think, is winning. There’s a reason why there have been, I don’t know, about 10,000 productions of On Golden Pond — because it does that. It takes the audience for the ride. Part of the thrill of the exchange between writer and audience, or reader, is, “I’ve got a puzzle, and I’m going to give you a few pieces so you see if you can put those pieces together in the correct order. Tell me what you find.” I definitely do that with Archie. Nobody knows what the hell is going on in that play at the beginning. I have one bugaboo, and that is, I don’t like, as a reader or an audience member, to be talked down to. I don’t like to have stuff explained for me, because then I’m thinking, “Why am I here? If you’re going to tell me everything instead of showing me and letting me stitch everything together, then you’re wasting my time.” There’s one guy I play volleyball with — and you’re thinking, “You’re still playing volleyball?” I am! — but this guy is the next closest in age to me, and he came to see the play. Every time I’ve seen him since, he has these piercing, deeply thought questions of, “Now, when he said this…” and, “Was Archie bullshitting the whole time when he told the story about his wife?” And I’m thinking, “Yes! That’s why we do this — to elicit that kind of audience response.”

Theater Mirror: We are given the suggestion that Archie is not the most reliable narrator. In fact, he might not have known the people he’s eulogizing at all.

Ernest Thompson: He worked in marketing, so of course he’s not going to be honest. But it also gives me an opportunity to talk about what that means. What does being honest mean? There’s a line in there where a therapist says, “Lying might be the new national official language, but we still have to be honest to ourselves.” At some point, we have to tell the truth. I think many people, if not most, go through life kind of in denial about circumstances, finances, relationships, sexual identity, whatever. At some point I just think, “Am I telling the truth?” I just love that as an underlying concept of Archie.

Theater Mirror: In your bio, there’s a mention that you have directed or written for something like three dozen fellow Oscar winners. In that process, what did you pick up from them that you could incorporate as a writer, as a director, and as an actor for yourself?

Ernest Thompson: First of all, I want to clarify. I didn’t write for all of them. I acted with, wrote for, and/or directed. So, it’s not as if all these people lined up for me to write stories for them. But I learned from every single one. The first one, I believe, was Rita Moreno, when I was starring on this TV show called Westside Medical in the ’70s. First of all, I fell madly in love with her — not that she noticed, but she was just so extraordinary. She carried a confidence.

This is parenthetical, but I think that is the real gift of being awarded something [like the Oscar], because you then are sort of gratified someone is looking at you and thinking, “Okay, this person has something to contribute.” Once that happens — I’m so grateful that happened early in my career — there’s a level of acceptance, even if you doubt it yourself. If ever I have doubts, which is only every day, I can go down to my library and there’s this little shiny trophy down there, and I can think, “Oh, okay, so maybe I’m okay at what I do.”

But the answer is, all of those people who had been endorsed carry a degree of that themselves, and it’s true of everybody I’ve worked with who’s had that sort of validation. I did learn from that, that it’s okay to feel proud of what you’ve done, and it’s okay that you got a pat on the back. That helps. I have this theory that nobody normal would be drawn to the entertainment business, because if you’re normal, you don’t need the approbation, but you also don’t need the rejection [and] all the other shit that comes with being in the entertainment business.

As a director, when actors come in to audition, my question isn’t, “Do you have talent?” Because probably the person has to have some sort of endorsement, or they wouldn’t have gotten in the door. I want to know how crazy you are, and is it a crazy I can work with? We’re all nuts, and it’s going to come out in some way. When I came into the business in the early ’70s, I had a sort of mentor whose name was Richard Coe. He was a great critic for The Washington Post, and he kind of took me under his wing and introduced me to a wealth of people who were friends of his, like Helen Hayes and Carol Channing. I would play sponge and absorb everything that they had to offer. I think they liked that I was a young acolyte just wanting to learn from them. That’s been true all the way [through my career], and I feel really blessed that I’ve had that exposure to people have set an example. They may be nuts — in the book I’ll never write, I’ll maybe tell the truth about some of them — but it doesn’t matter, because they do what they do, and lucky me that I’ve gotten to spend time with them.

Theater Mirror: There’s more than one wink at contemporary politics in Archie Parish’s Parting Words. You also have one-act play, The Constituent, that you’ve recently turned into a short film that tackles politics. Was that sensibility always there, or are you writing more about politics now?

Ernest Thompson: Well, the politics is always there in my head and in my heart. One has to be judicious about how big a slap in the face it’s going to be for the audience or the reader [for a work to say something about politics].

I believe there are five basic tenets to successful writing. The first one is emotion — everything I write is deeply emotional. Then it goes character, plot, dialogue, message. When I teach workshops, I say to writers, “If you’re not putting the message in, however obliquely, you’re wasting an opportunity.” It doesn’t have to be a sermonette, but if you can open the door to conversation, to thinking — man, wow. Many of my friends are perhaps not quite as progressive and liberal as I am. I don’t have Trumpies in my life at the moment, but there’s a lot of middle ground, and I like putting questions out there and letting them answer the questions for themselves.

So, The Constituent — I don’t know if you know this, but I wrote it before On Golden Pond. It was one of my first one-act plays. [It was] 1977, I was turning 28, and I stayed up all night to finish these three one-act plays, collectively called Answers, because I wanted to finish something. I wanted to establish my pole in the sand that I was a writer. The Constituent was very political. In 1977, it got taken under option. Eventually, we did a TV special with Burgess Meredith and Ned Beatty. [Note: The 1985 TV movie also adapted the other two short plays in The Answers, with Sam Bottoms and Patty McCormack starring in the segment A Good Time and Robert Webber, Eileen Brennan, and Kenneth White starring in the segment Twinkle Twinkle.]

Because I can’t sit still very long, I have this play sitting here, and [fellow actor and New Hampshire native] Gordon Clapp and I think, “We should just do it.” We started on a zero budget. We got another wonderful actress, Lisa Bostnar and we just shot the thing. Its politics are pretty bare; however, when I wrote it, I didn’t think about picking up the play and adapting it. I wrote the play that I remembered, and I flipped the politics unconsciously. So, the character I play is this crusty old woodsman who writes letters to his senator, and somehow the woodsman has become progressive, and the senator has become more like what most senators are now. It opens up a door for conversation, which I love.

And, of course, I also write songs. I’m not shy in writing protest songs, and I think it’s a valuable tool right now. In The Constituent I wrote a song called “Cross the Bridge” with a great guy from Maine named Griffin William Sherry. I have a new song called “You Bought It, You Own It” — you can probably guess what that’s about. And, I have a new song called “My America.” I’m not singing them, but I just love having that tool as well, that I can employ. I don’t have time to go march at every demonstration, as I did in the ’60s, but I feel I can make a contribution by just putting that stuff out there.

Theater Mirror: In this play, as well as in On Golden Pond, you find a way to bring us to a hopeful ending. But I do wonder about your idea for an ideal happy ending — or if that’s even something that’s necessary.

Ernest Thompson: Well, I’m so glad you asked that question. One of my little conceits is that I believe in the three H’s: Heart, Humor and Hope. If a story doesn’t have those three items, I don’t want to be in it. I don’t want to write it or direct it. People have said, “Why doesn’t Norman die [in On Golden Pond]? You know, he’s having a heart attack.” I said, “Because of Dr Zhivago. Because when I was a young guy, I saw Dr Zhivago, and Omar Sharif is on a trolley in St. Petersburg, or wherever he is, and he sees Julie Christie walking down the sidewalk, and he runs out after her, and he falls down and dies in a snowbank — and she never turns around.”

There’s no illusion; Norman Thayer is going to kick the bucket in a month or a year. He’s losing his mind [to dementia]. I’m not trying to whitewash that. I’m just trying to say, “Wouldn’t it be nice to have hope in our lives?”

And it’s true of Archie. You know, Archie could have just said, “Fuck it.” [But he doesn’t] because I want the audience to walk out and think, “Yeah, so what is it in my life that I should feel hopeful about? Because it’s not the happy ending business.” There was a program on years ago, I think it was on Dateline, where a therapist talked about what happened with Chelsea and Norman in On Golden Pond. It’s not that they solved all the problems of the world; it’s that they took baby steps toward each other. There was a suggestion of détente, and that’s all I asked for in life. I want people to walk out of a theater or put down a book and think, “Okay, so for the minute, we’re going to be okay.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

For more about Ernest Thompson, check out his website: https://ernestthompson.us/ .