‘Our Class’ – Written by Tadeusz Słobodzianek. Adapted by Norman Allen. Directed by Igor Golyak. Staged by Arlekin at the Calderwood Pavilion at Boston Center for the Arts, Boston, through June 22.

By Shelley A. Sackett

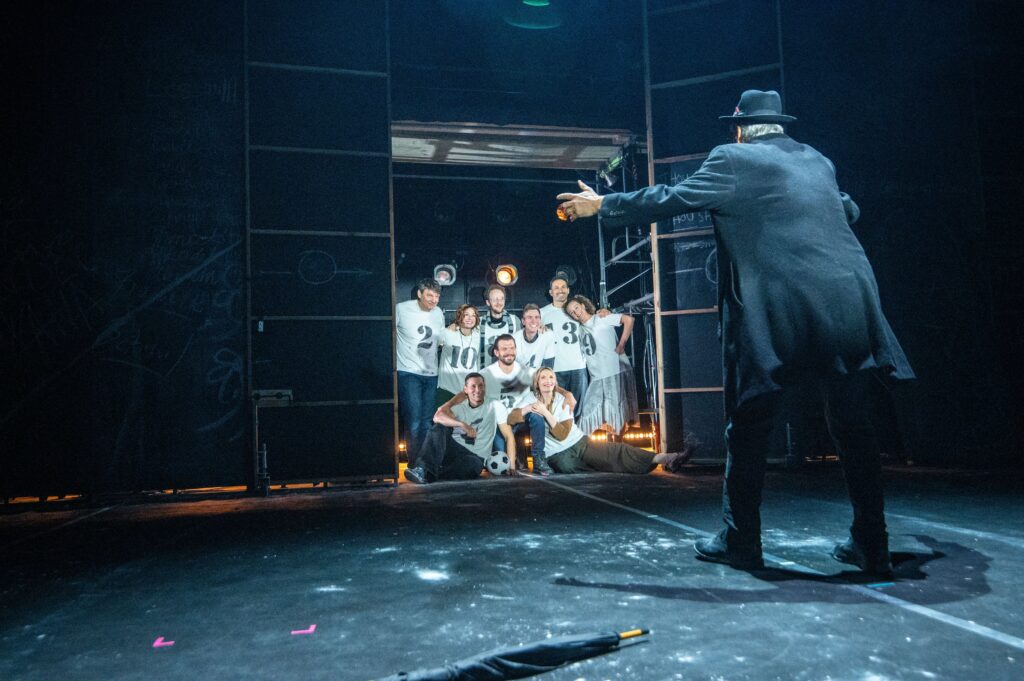

No one can take his audience on an emotional and artistic roller coaster like Igor Golyak, founder and artistic director of Arlekin Players Theatre & Zero Gravity (Zero-G) Theater Lab. With “Our Class,” in production through June 23 at the Calderwood Pavilion, he introduces us to characters we initially relate to and bond with, spins an artistically ingenious cocoon, and then tells a tale that rips our heart to shreds and leaves us too overwhelmed to even speak.

Written by Catholic Polish playwright Tadeusz Slobodzianek in 2010 and inspired by the true story of the 1941 Jedwabne pogrom, “Our Class” introduces a group of 10 young adults – five Catholic Poles (Zocha, and the “Four Musketeers” Rysiek, Zygmunt, Heniek, Wladek) and five Jewish Poles (Dora, Rachelka, Jakub, Menachem, Abram) – who have grown up in the small town of Jedwabne and have known each other since 1925, when they were all five years old.

Subtitled “A History in Fourteen Lessons,” the multiple Lortel Award-winning play follows these 10 from 1925 to 2003, through the upheavals of 80 years of history marked by rotating vicious regimes (Stalin’s Red Army, Hitler’s Nazi Germany, post-WWII USSR), increased brutality and genocidal antisemitism. Some will become victims, while others will become perpetrators. None will remain unscathed.

We meet these classmates in Lesson 1 as grade schoolers, singing songs and introducing themselves. The mood is light and welcoming. They tell what their father does and what they want to do when they grow up. As they speak, each character’s name, date of birth and date of death are written on the enormous blackboard that is the scenic centerpiece. Some will die in 1941; others as late as 2002. Before even hearing their stories, we already know who shall live (mostly Catholics) and who shall die (mostly Jews) and when.

Although Polish-Jewish relations were politically complicated then, these youngsters are merely curious about their differences.

All of that will change soon enough. The choices each character makes in response to these historical events determine the courses of their lives and the demons they will later battle.

In 1937 (Lesson 4), the four Catholic boys band together, turning as brutish and menacing as their government. They reject and betray their Jewish classmates. Catholicism is the “one true faith” and one brings a large cross to class for prayer sessions, “which means it’s time for our Jewish friends to remove themselves to the back of the classroom.” When the Soviets invade, the “Four Musketeers” commit atrocities that they blame on the Communists. When the Nazis arrive, they switch sides and continue preying on the Jews, including their classmates. Zygmunt (a terrifying Ryan Czerwonko) beats up Menachem for his new bicycle while Zocha (the always magnificent Deborah Martin), his Catholic sweetheart, watches helplessly. The four thugs laugh and then defiantly pray to Jesus.

That same year, Abram (the charismatic Richard Topol) leaves for New York, the only classmate who escapes the horrors about to unfold. He becomes a rabbi and sends letters home. As the unofficial narrator, announcing each lesson, his happy, settled life in America contrasts starkly with the chaotic ruthlessness of Poland, where friendships and loyalty devolve into violence, prejudice and even murder. When Jakub is suspected of being an informant, three musketeers beat Jakub to death and slit his throat in a gut-wrenching scene staged on a ladder. “They were my neighbors,” Dora flatly recalls. “I knew them. Just laughing. Making jokes.”

The Jedwabne pogrom took place in 1941 (Lesson 10), and 1941 is the play’s pivotal turning point. The town’s Polish citizens killed its 1,600 Jewish residents in one night by locking them in a barn and burning the barn down. These were ordinary people, including our musketeers, doing and covering up unspeakable things. Afterward, the perpetrators maintained that the Nazis were responsible for the massacre, a travesty that continued until a 2008 investigation revealed the truth.

Act I ends with the wedding between Wladek (the musketeer who watched, but did not participate in Jakub’s murder) and Rachelka (the renowned Chulpan Khamatova), the only Jew left in Jedwabne, in one of the play’s most gut-wrenching scenes. Wladek (wonderful Ilia Volok) has vowed to save her with one caveat – she must convert to Catholicism and change her name to Marianna. Shrouded in a white sheet with lipstick smeared across her face, she is a shell-shocked hostage, a dybbuk trapped in an earth-bound body. The three murderous musketeers shower her with wedding gifts of booty stolen from now-dead Jews. The despair in her eyes is shattering.

The play is full of such difficult moments, yet Golyak manages to blunt them with aesthetic elements that help the audience achieve some breathing space from the sheer horror. The opening scene, for example, is staged as a reading. Scripts in hand, the actors are in contemporary garb, evoking the timelessness and timeliness of the play’s issues. Characters draw faces on ghost-white balloons and set them free to float upward, a metaphorical gesture that lessens the impact of watching the inhumanness that might otherwise catapult us over the edge. Folding ladders, a bedsheet, original music and stunning lighting and projections all add to the production’s power and mystical aura.

The acting is indescribably sublime, each actor both a searing individual and a perfect ensemble member.

That the play is rooted in a true story makes “Our Class” feel like an important history lesson, especially in these times of revisionist history, mob mentality, “othering” and seemingly insurmountable global antisemitism, violence, and raw hatred. The questions Slobodzianek poses are no less pertinent today than they were 80 years ago: Who is more to blame, those who incite, those who bear silent witness or those who act? Does it even matter? How do boys become murderers and friends betray friends? How do you know and tell the truth when there are so many to choose from? And most of all, how do you go on as a survivor of such trauma?

Marianna and Wladek stay married until the play’s end. Marianna reflects on her life with ambivalence and resolve, summing it up in seven little words that have become our mantra: “We Jews. We’ve survived such things before.”

For tickets and additional information, go to: arlekinplayers.com.

(Editor’s Note: This review previously appeared in The Jewish Journal)