“I was born in Russia,” New York-based theater maker Irina Kruzhilina explains as our interview commences. “My mom was born in Ukraine. My father’s a Georgian Jew, which makes the situation right now, as you can imagine, very difficult. But I think that most people who are in Russia, or those who escape, do have this background, whether it’s Russian-Ukrainian or Russian-something else.”

Raised in Moscow during the days of the Soviet Union, Kruzhilina witnessed the transformation of Russia first-hand… and then witnessed its reversion. “I moved here the year Putin became the president,” she recalls. “I immediately moved to the States, where I got my second master’s in theater and started working. I have training in theater design, and I got additional training in directing.” That training stood Kruzhilina in good stead last year when she did the scenic design for Arlekin Players’ The Gaaga — work that earned her an Elliot Norton Award.

“I design, I write, I direct, I teach, I co-created an MFA program at the New School, which is a program on contemporary performance where we do not have separation between playwrights, directors, and actors, and they get the experience in collaborative theater making,” details Kruzhilina, who is also the founder of Visual Echo — “a New York-based performance organization fostering generative dialogues among people from diverse backgrounds who rarely intersect,” as her bio at The New School notes. “And,” she adds, “most of the projects which I do have a big social justice lens.”

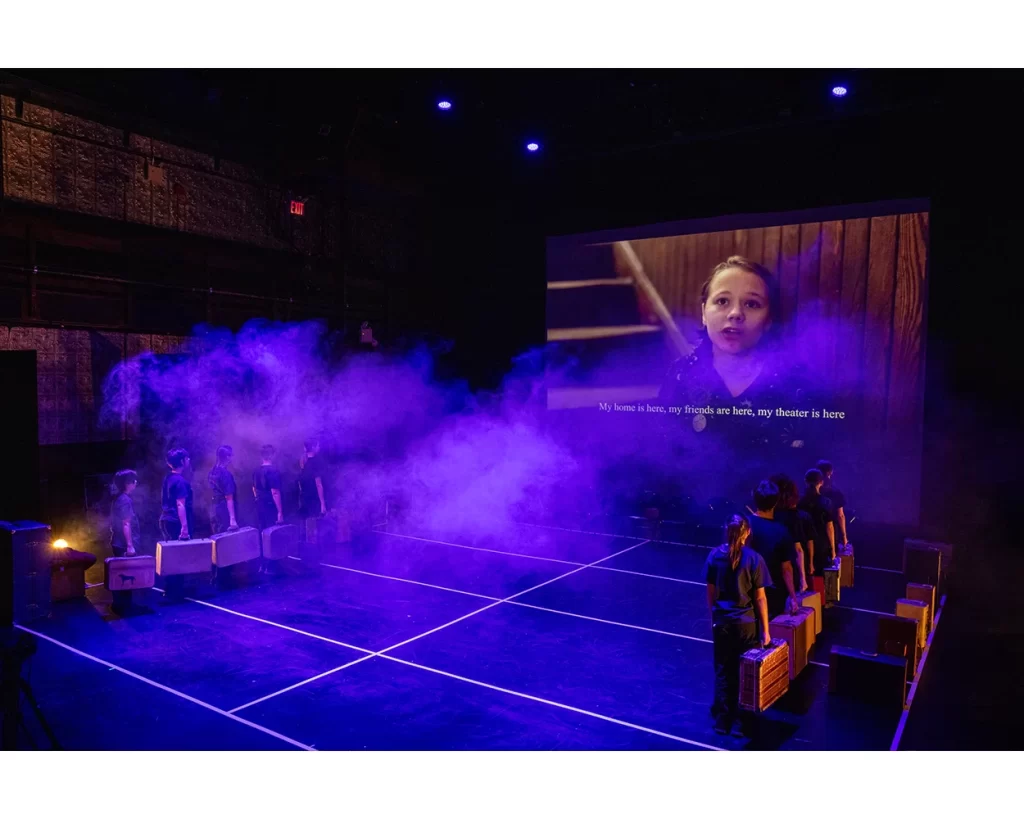

That’s the case with SpaceBridge, which Kruzhilina is bringing to the Emerson Paramount Center, courtesy of ArtsEmerson. The play, which runs for an hour and a half, will have four performances, November 21-23. The social justice issue here is one regarding refugees fleeing the effects of Russia’s war with Ukraine, but not the refugees you might expect: What the production relates are the true experiences of Russian children whose parents fled due to Russia’s crackdown on dissent, or even criticism, of the war. Far from being welcomed with open arms, these displaced families face a labyrinthine bureaucracy and a hostile society… not in some foreign land, but here in the United States.

The play’s title comes from a series of then-cutting-edge satellite-enabled video calls in the 1980s and 1990s that put ordinary citizens of the United States and Russia into direct (if electronic) communication. The idea might be decades old, but the spirit of dialogue that Kruzhilina and co-writer Clark Young seek to establish is timeless… and as crucial now as ever.

Kilian Melloy: Theater has been a huge part of American culture. Is that equally true in Russia?

Irina Kruzhilina: Theater is a massive, massive part of Russian culture. When I grew up, it was still the Soviet Union. We had to go to the theater twice a week in school — it was part of our education. Theater [was] just what people did; people would go to the theater, they would go to the cinema, I would say, once a week. People would not go out to eat, because that was not a part of the culture. And people still go; the last time I went, before the pandemic, it was Tuesday evening, and everything was sold out. There are, like, 200 theaters in the center of Moscow, but I could not find a ticket to go and see a performance, which was very inspiring.

Kilian Melloy: Did theater in the days of the Soviet Union find ways to say things that were otherwise not permitted?

Irina Kruzhilina: You could not put a lot in the text, because that would be censored. So, the way to communicate the message to the audience, which is a very smart audience, was through staging and through visuals. It was very metaphorical and not very prescriptive. I often find American theater to be more prescriptive and more educational, rather than emotional. Growing up with Eastern European theater, it was really, ‘How can we communicate something through the use of visual metaphor?’ The audience is still getting the same message, but the government does not. Now, Russia is back in the same dictatorial regime, so I think [theater] went back to being more metaphorical.

Unfortunately, most of Russian theater makers [have] moved to different countries. They didn’t stay in Russia. It’s just [too] dangerous. I don’t know if you’re aware, but there are playwrights and directors who are in jails in Russia at the moment. I would get arrested at the airport if I [were to] go to Russia right now, actually.

Kilian Melloy: Space Bridge is what they called a series of satellite-enabled live video exchanges between Americans and Russians. Today, we could have a Zoom meeting, like we’re doing right now, or we can talk to people on Facebook, but do you think that similar video calls between the people of Russia and the people of the United States could still be beneficial?

Irina Kruzhilina: I hope so. Actually, Space Bridges were the only communications between the two countries which were not censored, and they were only common folks [participating]. That was really the first time when we saw that you guys were the same as us, because when we were growing up, we were sure that you had four arms and two heads and were evil, and I’m sure it was the same in the States. And that is really what I believe ended the Cold War. [The fall of the Berlin Wall], Gorbachev and Clinton, that was all part of that later. But what really helped is the common people talking to other common people, understanding that they have more in common than [not], and how much propaganda was happening in our lives back then.

I think it’s the same right now, and I think there is much less appetite for people to connect across two cultures than back then. I’ve lived here for 25 years, but I think that the assumptions which two countries have about one another are really strong. Even with all the technology at our fingertips, we [cling to] certain ideas. Please don’t get me wrong: There are things which are simply evil, and where there is absolutely no nuance, which is happening with the war [in Ukraine] and with politics. But there are also people who are deeply admired who stayed [in Russia], and who are jailed multiple times and [who are] fighting. I think we need to know about them as well. If there is a way to bring Space Bridge back, it would be wonderful, because at some point, we need to figure out how the two countries can exist in the world. I don’t think this world will survive a war between the two.

Kilian Melloy: What was the origin of the idea to create this theater piece and to let children tell their perspective?

Irina Kruzhilina: I started before the war [in Ukraine], actually, and I started it connected to the previous question you asked: Can Space Bridges exist now? I wanted to connect one school in Russia and one school in America to see if we can connect the children. The idea of children came from Samantha Smith, who is a character in this play, [imagined as] if she was alive today. Interestingly, people don’t know her in America, but in the Soviet Union, she was the biggest star, like Michael Jackson. She was a girl from Maine who wrote a letter to Andropov in 1983, asking why he wanted to destroy America. He wrote her back and invited her to come to the Soviet Union. She met a lot of friends her age, and then she gave a press conference where she said, ‘They actually like us. They don’t want the war.’ And she suggested that Andropov and Reagan exchange granddaughters, because if they did that, there would be no war. She had this very simple and creative idea of how cultures can find peace.

If we can channel these ideas through children, maybe there would be a way for the cultures to connect again, so I started with the schools. I started it in February [of 2022], and then the war started at the end of February. I had to immediately stop both for ethical reasons, and also, it would not be safe for teachers and parents in Russia to talk to the Americans anymore.

For the first two years, I was just supporting Ukrainian playwrights, but I was also alerted by a lot of refugees who were coming here from Russia — not only Ukraine — and I read about their experiences. A lot of them came with families, and many of the children were really bullied in schools. I worked with some kids who were called fascists at the age of 10. I was trying to figure out, ‘If Samantha was alive, how would she connect the children?’ I decided to work with children, and found them through shelters, through friends, and it was very important for me to tell not only their stories, but the stories of their friendships with American kids.

Kilian Melloy: Can you say a little more about how you went about collecting and integrating the stories that you include in the work?

Irina Kruzhilina: We started as a workshop program, preparing some creative exercises. [The children] would answer certain questions, or write stories, or write their memories, or draw things… [it was] me giving creative prompts, and then editing [the responses] and combining them into the script. The structure of the scenes came from me, but all the material is really written by children.

Kilian Melloy: Many people fear that the United States is on the same road that Hungary took, and that Russia took under Putin. Is that something that concerns you?

Irina Kruzhilina: This is a déjà vu for me. This is the reason I left Russia. We’re following exactly the same trajectory right now, except what took Putin 15 years [in Russia] took two months [in the United States]. Guys, it’s too early. It’s too early to be afraid to go on to the streets. It’s too early to have this paranoia. If we’re just scared, we’re going to end up in the same place as Hungary, and Russia, and China. We hope not, but it might happen. America was never under a dictatorship, so I think that people don’t believe that it can happen here, but it can. I recognize the patterns, and so SpaceBridge is essential right now.

Kilian Melloy: You’ve already presented SpaceBridge at the off-Broadway theater La MaMa, where you are a resident artist. What was the audience response?

Irina Kruzhilina: It was very beautiful. We had teachers, we had parents. We had friends of American parents who were really supportive. The American parents are extraordinary. We had shelter workers, we had students, we had young people. We had a lot of immigration lawyers, in addition to the downtown theater audience. So, the audience was extremely engaged, and they took it as a call to action. There were two lawyers who wanted to represent the families, and we connected them. There were shelter workers who wanted to change the policies at the shelters. And there were teachers who are changing some things in their schools.

Many in the audience were not aware that there is such a thing as Russian refugees. [Russians] are all seen as evil, and [people] never think about how they also have stories to tell. There is room for more than one group of children to empathize with. That was a discovery which they found, and that’s very important. But also, the show is very funny, and that was really important, and it’s very beautiful. I’ve rarely seen a more engaged audience, to tell you the truth, and a more diverse audience. I think that’s important.

Now to do it in Boston, which is a different animal and not very familiar to me. It’s going to be different to travel with 20 children.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. ‘SpaceBridge’ runs at the Emerson Paramount Center’s Robert J. Orchard Stage from November 21 through November 23. For tickets and more information, visit the ArtsEmerson website: https://artsemerson.org/events/spacebridge/