Photos by Joe Kenehan

‘Death of a Salesman’ – Written by Arthur Miller. Directed by Robert Kroft; Scenic Design by Justin Lahue; Lighting Design by John Malinnowski; Projection Design by Justin Lahue and Katherine Wittman. Presented by Harbor Stage Company, 15 Kendrick St., Wellfleet, through August 2.

By Mike Hoban

One of the driving forces behind the 1960s counterculture movement was the realization that the metrics used to measure success in American life were fundamentally flawed – that the American Dream was, for many, bullshit. Expecting to be rewarded for loyalty to a company, believing that money could buy happiness, trusting that fidelity and mutual respect were inherent in a marriage, and buying into the myth that America was the moral compass for the world were all wonderful ideals, but ones that often failed to meet the unforgiving test of reality. There are few works that better exemplify that school of thought than Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, now being given a darkly brilliant staging by the Harbor Stage Company in Wellfleet.

Set in post-World War II Brooklyn and told in real time punctuated by flashbacks and hallucinations, Death of a Salesman is the story of Willie Loman (William Zielinski), the title character who has bought into that dream wholeheartedly. As he tells his boys in a hallucinatory monologue, “The man who makes an appearance in the business world, the man who creates personal interest, is the man who gets ahead,” he preaches. “Be liked and you will never want.” It’s a flimsy premise to build a life on, and one that will make his descent into hopelessness inescapable.

When we first meet Willie, it’s the middle of the night, and he has returned unexpectedly from an aborted business trip to Boston. He’s unnerved and demoralized, and his doting wife Linda (Stacy Fischer), who has become increasingly concerned about his mental health, is there to comfort him. She suggests that he ask his boss to take him off the road and give him a territory closer to home, and he reluctantly agrees. Meanwhile, his son Biff (Alex Pollock), a 34-year-old former football star who has drifted aimlessly since high school, has returned home for a visit, and Happy (Jack Ashenbach), his moderately successful, philandering brother, are bunking for the night in their boyhood bedroom. They, too, are concerned about their father’s cognitive decline, and the returning Biff is mortified that Willie has begun talking to himself out loud in an animated manner.

Willie and the underachieving Biff have a longstanding, strained, and often hostile relationship. Willie constantly harangues Biff about his lack of direction in life, imploring him to follow in his footsteps, chasing the American Dream, completely unaware that he is a walking billboard for why that strategy is often a recipe for failure – especially for men like Biff. As the defeated Biff tells Happy, “I’ve always made a point of not wasting my life, and every time I come back here I know that all I’ve done is to waste my life.”

Willie is also figuratively haunted by the ghost of his deceased, successful brother Ben, whose disembodied offstage voice reminds him, “When I was seventeen, I walked into the jungle; and when I was twenty-one, I walked out. And by God, I was rich.” Instead of taking pride in what his brother accomplished through hard work and initiative, it serves as a blistering reminder for Willie of his own failures, especially after he loses his job following an angry confrontation with his boss. These disharmonious ingredients come to a rolling boil in the second act of the play, where the defining moment of Biff’s promising life going off the rails is revealed, and the downward spiral of Willie comes to its inescapable conclusion.

Given the rise of the gig economy and the rejection of traditional work life by many (particularly Gen Z) workers post-pandemic, Death of a Salesman works best as a period piece, even as capitalism prepares to finish off what is left of American democracy. Harbor Stage has produced a masterpiece in the confines of its intimate theater, and its black-as-coal themes stand in stark contrast to the usual summer theater fare.

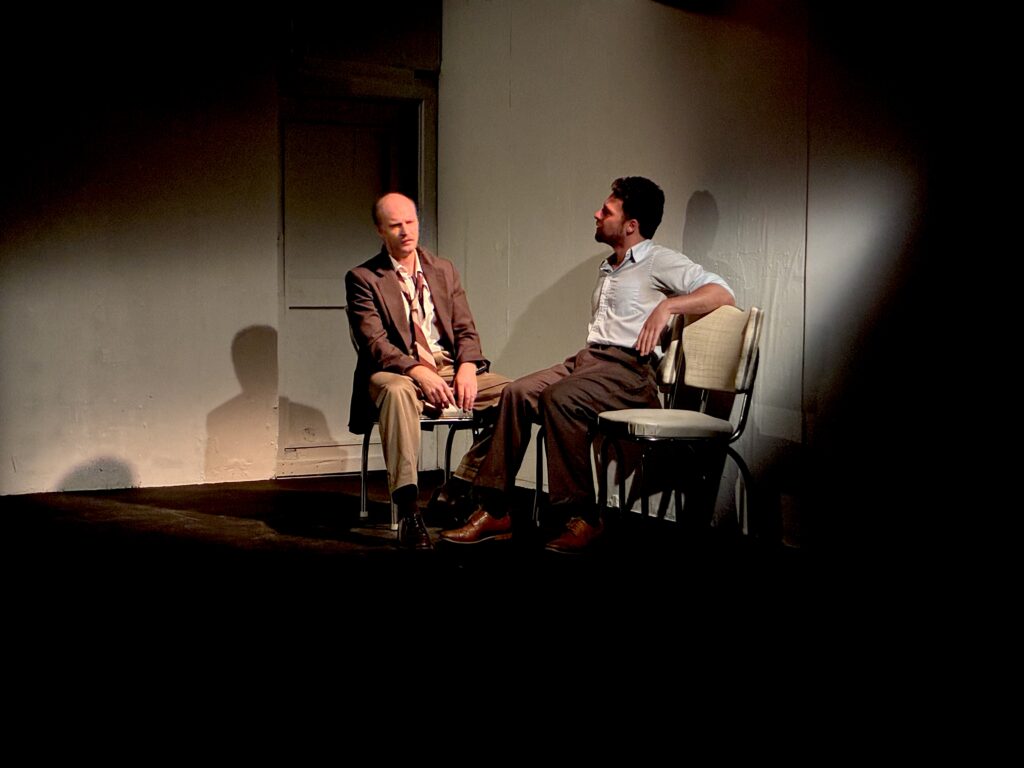

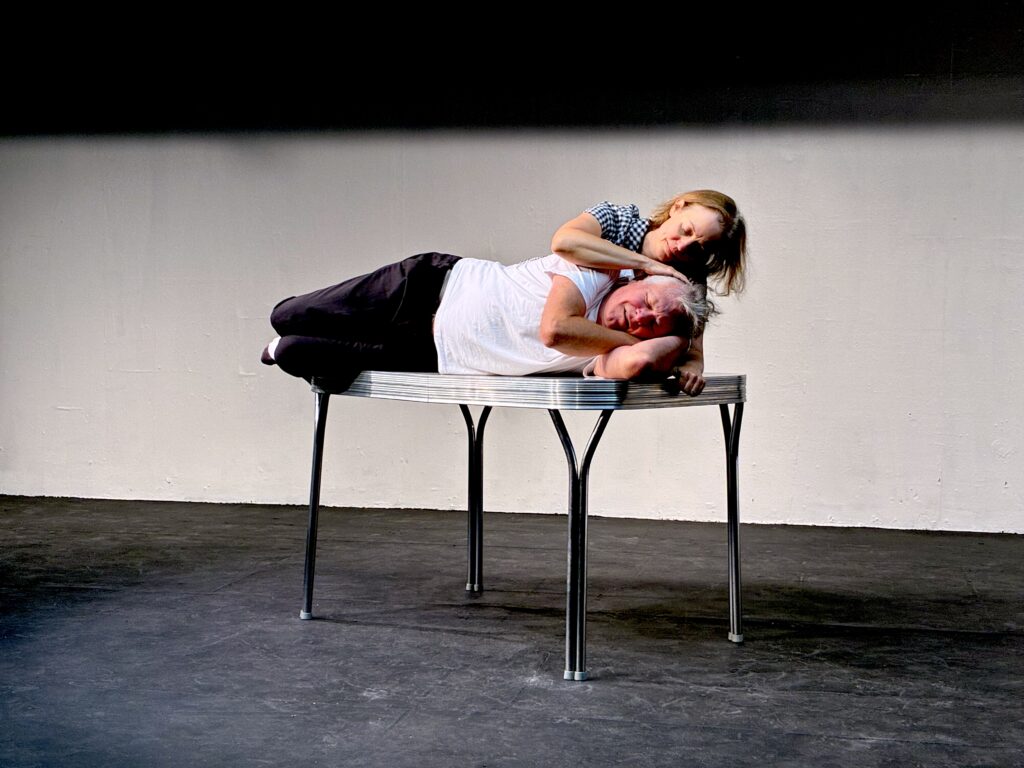

Director Robert Kropf has stripped the production down to its bare bones, including relying on live projected images of secondary characters and settings on the walls of the set in place of complicated scene changes (conversations with his helpful neighbor Charley, Willie’s hotel room in Boston, etc.), which can be a little confusing for those unfamiliar with the play. Scenic designer Justin Lahue’s set could not be more minimalist, with antiseptically white walls and a handful of props (literally four or five chairs and a multipurpose table), which, in conjunction with John Malinowski’s bold choices in the lighting design, creates a surreal atmosphere for conveying Kropf’s artistic vision.

This leaves the production in the capable hands of Kropf and his outstanding cast. Zielinski’s Willie is less pathetic and more aggressive than I have seen in other productions (most notably Dustin Hoffman’s movie performance), but it’s no less compelling. Pollock gives a beautifully tortured performance as the disillusioned Biff, and Ashenbach portrays Happy’s self-centered womanizer with an ambivalent charm.

Fischer is the one who steals the spotlight, however, delivering a masterful performance with her portrayal of Willie’s put-upon wife, Linda. The unwavering love and devotion she shows to her deeply flawed and prideful husband borders on the delusional, but it’s her explosive reaming of Biff and Happy for not giving their father the love and support (that he may or may not deserve) in his darkest hours that makes this portrayal so three-dimensional. In a career that has earned Fischer repeated recognition from the Eliot Norton and IRNE Award committees, this may be her finest work.

The Harbor Stage theater may be a trek for Boston theatergoers (unless you’re lucky enough to be vacationing at the far end of the Cape), but it’s well worth the ride. Tickets are nearly sold out, so don’t hesitate if you’re intrigued. For tickets and information, go to: https://www.harborstage.org/