Najee A. Brown’s Stokely & Martin imagines a pivotal dinner conversation between Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) — Stokely Carmichael, Cleveland “Cleve” Sellers, and Willie Ricks — in 1966, at a moment when the civil rights movement was fracturing over questions of tactics, philosophy, and the meaning of Black Power.

Brown, the Artistic Director of the Multicultural Arts Center, wrote and now directs the production. The script comes with an imprimatur of authenticity: The dinner table conversation (a “strategy room” session, Brown explained during our interview) is informed by interviews Brown did with Willie Ricks, who attended just such gatherings. “They knew strategically what they had to do,” Brown notes, “and they did more planning than they did marching. Now I feel like we do more marching and maybe some planning that I don’t know about, or no planning at all.”

Indeed, the current moment cries out for revisitation and reexamination of the struggles and triumphs of yesteryear, lest what hard-won progress was gained evaporate and oppression and marginalization of certain minorities (be they racial, ethnic, religious, or otherwise) by empowered factions with no love for equality or the rule of law once more become the order of the day. “We have to look at the examples” King and other civil rights leaders set, Brown argues; “not just the glorified version of it, but the hard work version.”

Brown spoke with Theater Mirror recently about the play, its contemporary resonance, and what we’ve lost in the decades since those leaders fought for liberation.

Kilian Melloy: Why set the play at a dinner at King’s house, rather than a back room or motel room somewhere?

Najee A. Brown: Food has always been an integral part of Black culture, so it’s important for these men to be having this conversation over a meal. By setting it in the kitchen where you see Coretta cooking, and seeing in the living room Martin working on a Sunday sermon, you get a glimpse of what Martin was like at home, where another play that may take place in a motel room or an imaginary other place, you don’t really get the at-home feeling that you get with this play.

Kilian Melloy: Although the play is titled Stokely & Martin, it feels like Coretta Scott King is just as much of a character, and just as important to the story, as either of the two of them. She’s so articulate and so clear in her understanding of what’s right and what’s necessary.

Najee A. Brown: Yeah, and that was a recent add. Five years ago, when the piece was first presented, Coretta came in and out very quickly. The play was shown at a college. Someone asked me for my address, and they mailed me a copy of Coretta Scott King’s autobiography. Since then, I’ve worked on another play about that family called Here Her Sing for Freedom, which was a musical about Coretta Scott King, so now I have all this research and understanding about who she was as a person, and knowing that she spoke out against the war way before Dr. King ever had the courage to. Yes, the optics were different, and she didn’t have as much to risk; but they were tied together, so she did have a lot to risk. But she spoke out against the war, and every day encouraged him to do so, too.

Kilian Melloy: It seems like she’s a voice of conscience, but also a voice of humility. All she has to say about a meal she prepares but doesn’t even partake in is, “The revolution has to eat.”

Najee A. Brown: Yeah, she does, and that’s the beauty of her. I feel like she grounds him. Every scene where you see her come on stage, there’s a groundedness where he can rest his head. She can grab his hand for comfort. She can straighten his tie. Every scene where she’s present, every word that she speaks is almost like, “I’m grounding you. You don’t have to be Dr. King around me. You can simply just be Martin.

Kilian Melloy: You’ve noted that the play centers on the struggle over Black power and what that means, and who gets to define it. Would you say the question has really been resolved even now?

Najee A. Brown: No, the question hasn’t been resolved. I think what they were trying to do, in terms of their message of Black power, was help us understand our identity a little better, especially after centuries of slavery and beatings and just being separated from our families. It was important for us to understand that there was beauty in our blackness — not taking away from the beauty of anyone else but understanding who we are in this world. And I still think, even though we’ve gotten a lot better, there are aspects of Black culture that can sometimes struggle with understanding our greatness, because a number has been done to keep it out of our plain sight. It’s important for me to highlight not just Dr. King and Malcolm X, but also all these forgotten figures in the civil rights movement. So, putting Cleve Sellers, putting Willie Ricks, putting Stokely Carmichael in this play is so important, because by just saying, “There was a man named Dr. King, and he did this, and he did that,” we take away from how great this movement was by just highlighting one person.

Kilian Melloy: You also give a shout-out to Bayard Rustin, which I was so happy to see.

Najee A. Brown: Yes, yes, yes, yes. Bayard Rustin, you know, because of the work of Adam Clayton Powell and some others, he got kicked off of Martin’s team. However, a lot of the thoughts and a lot of the inspiration that Martin had, especially in the early Montgomery Bus Boycott era, was really him. Coretta speaks about hearing Rustin speak at Antioch College when she was young, and I think they developed a relationship there, and that was life-changing for her. So, she had knowledge about him before Martin did. But him being Black and gay at a time where it was bad to be both definitely keeps him out of the conversation when he should be studied and honored, too.

Kilian Melloy: You let us see King at a moment when he’s very uncertain and wavering, but you make it into a moment that is heroic.

Najee A. Brown: Yeah, he is heroic in this, and this is one of the last decisions that he gets to make, one of the last sacrifices he gets to make. Obviously, he sacrificed his life, and I’m not comparing him to Jesus, but he did sacrifice his life for the betterment [of others]. For me, this is one of the most pivotal sacrifices that takes him from being a little unpopular to very, very unpopular. Right before he died, his approval rating was, I think, in the 20s or 30s; he was one of the most unpopular public men in American history at that time because of where he took a stance. I honestly believe that’s why he was murdered. Like he said in the play, it’s one thing to make someone use the same bathroom as somebody else, but when you’re standing against something that is global, when you’re talking about the Poor People’s Campaign, when you start fighting for health care for not just Black people but for white people, then you become a real danger. He knew that, and he still made that sacrifice. How many people are willing to make those sacrifices today?

Kilian Melloy: We had so many extraordinary leaders at that time, and now it seems like there’s nobody like that. Do you see anyone who could be our generation’s Martin Luther King or Malcolm X?

Najee A. Brown: I think these men knew an important principle. And forgive me if this is too biblical, but it is hard to be a pharaoh and it’s hard to be a Moses at the same time, and I think a lot of them thought that they had to go into politics. And I think it’s very impossible in 2026 and back then, to be a very clean politician. I think the closest we probably got to that was Bobby Kennedy, and as we know, he never made it to become president, but I think that was probably America’s last hope for a social justice consciously minded president, And I say that because Dr. King never ran for office, but a lot of the men after who were part, I think they thought that was the answer, and shifting from civil rights to going, you know, ‘I’m going to be in the room where it happens.’ I think you can’t get involved with this country without getting your hands dirty. And I’m sorry to say it like that. It’s just the truth.

Kilian Melloy: With ICE murdering people in the streets and the current administration seeming to have declared war on half the country, it feels like we are right back in the tumult of the 1960s. Or maybe this has always been simmering under the surface?

Najee A. Brown: It’s kind of weird. About two or three weeks ago, I was sitting there with my cast saying, “I’m not sure how relevant this play will be.” Then Venezuela happened, which is very similar to Vietnam, and then the ICE agents’ murders just came out of nowhere, and then this whole conversation about policing in Minneapolis is coming back. Honestly, this is the same exact temperature that I wrote this under when I wrote it five years ago, when George Floyd was murdered. It’s weird how you can ask yourself if a piece of writing is even relevant, and ‘should we be having this conversation?’ And then America does its number again, and it feels like we’re back where we started.

And you’re right, it’s always been there. But I think what’s different now is that — and it was important — you asked, why this setting, the strategy room [meeting at Dr. King’s house]? By the time they got to integration in 1965 — this was told to me by Willie Ricks, [the basis for] one of the characters in the play — they weren’t even able to meet in hotels anymore, because integration kind and having an emotional experience, holding signs and crying, hugging and singing “We Shall Overcome” and “This Land is Your Land, This Land is My Land.” It is them having strategy and vision paired with them. That’s what lacks in today’s movements. We have “No Kings” marches, [but] there’s no clear strategy from point A to point B, where we want to go. When these people went out and spoke, and when they went out to march, there was so much strategy with it. The Bible says — and now to put on the reverend hat, because we are in the spirit of Dr. King — without a vision the people will perish. We need vision more than ever.

Kilian Melloy: You zero in on this moment with an imagined conversation between him and the Black Power leaders, and they’ve got very different philosophies.

Najee A. Brown: Yeah, they do. But a similar goal, which is the liberation of an oppressed people, and I think that’s where they get to at the very end, I love you. I thank you. I’m grateful for your sacrifice, and I see you. These conversations really did happen, and they really did sit around the table and discuss these, these very topics. Of course, I don’t know exactly what was said and how it was said and what was said, and I have interviewed Willie Ricks, who was there.

Kilian Melloy: What do you hope audiences take away from this play?

Najee A. Brown: You have two very different men with very different stances and very different plans on how to handle the world. Yet at the end of the day, they can sit around the table, and they can have a meal. And now you see with the left and the right, none of these people can now sit at a table and just have a dinner and say, “All right, what is the goal? What is it that we’re trying to do? And can I ask you a question, “Why do you believe in this? And why do you believe in that?” This play shows a very clear example of two men that could have easily become enemies once they went on different paths. They still remain in their friendship and still remain in their love for each other.

Kilian Melloy: What else might you be working on?

Najee A. Brown: Something happy!

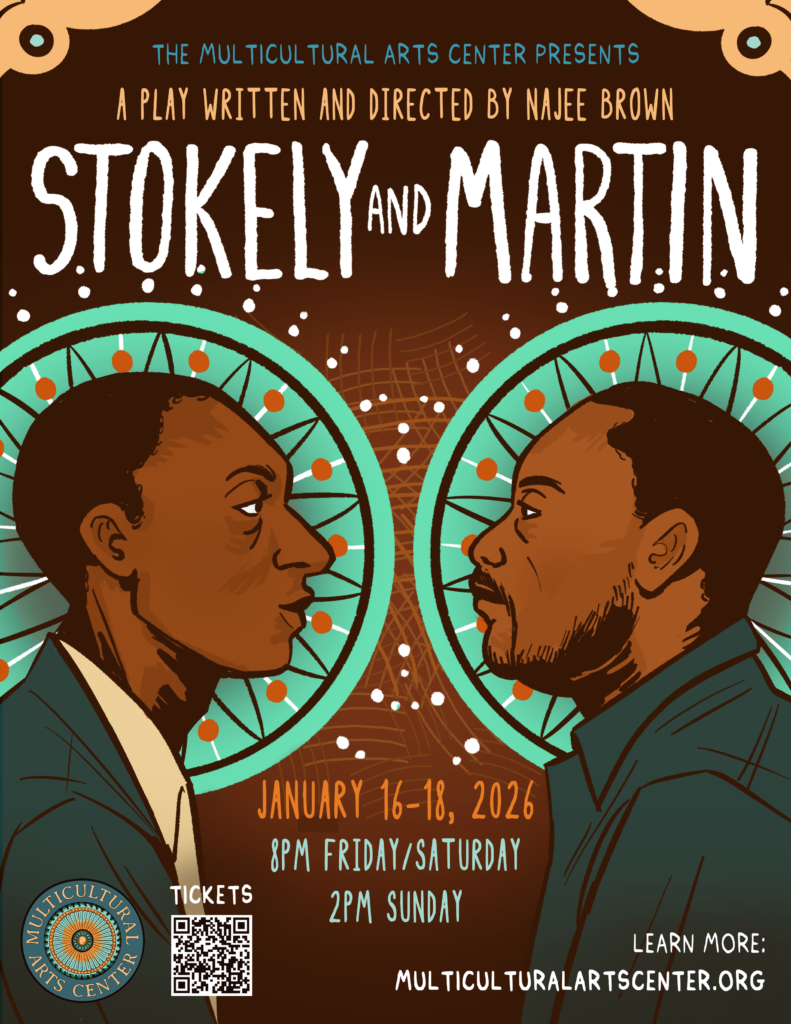

“Stokely & Martin” plays at the Multicultural Arts Center January 16–18, 2026. For tickets and more information, visit the website